The S&P 500 has evolved into an increasingly narrow, momentum-driven benchmark, raising questions about whether investors can still treat it as the broad, neutral representation of the US market it is assumed to be.

Several allocators argued that this shift could reshape both future returns and the index's usefulness as a default holding.

Simon Evan-Cook, multi-manager at Downing, said the changes are significant enough that the S&P could soon move from being “nigh on impossible for active fund managers to beat” to an index that becomes “exceedingly easy” to best.

Why concentration changes the odds for active funds

The mechanism is the same one that made the FTSE 100 difficult for active managers when banks, miners and energy names dominated performance. When the largest constituents power ahead, active funds struggle; when that leadership fades, markets become far easier to outperform.

“You don't even need to be a particularly skilful fund manager in the UK in the 2010s,” he said. “Literally, the average fund was beating the market.”

But the S&P 500’s concentration today is not simply the result of company fundamentals. It is increasingly shaped by automatic index flows, according to Joe Richardson, discretionary investment manager at Dennehy Wealth.

“The index is now driven by market cap and massive ETF [exchange-traded funds] flows rather than fundamentals,” he said. “It's a feedback loop where big stocks go up, they become a bigger part of the index, ETF money buys more of them automatically, they go further up. None of that has anything to do with valuations or earnings or sensible portfolio construction, it's just mechanical momentum.”

This narrowing of leadership is also why Richardson believes many investors misunderstand the risks they are taking.

“Owning the S&P isn't owning the US economy, it's owning a handful of the big tech companies,” he said. “It's incredibly narrow leadership, which has worked brilliantly in recent years, but it means your returns are tied to a small set of very expensive names. This is not diversification.”

With the index so dependent on a small group of mega-caps, he also questioned its relevance as a benchmark.

“Benchmarking yourself to the S&P is borderline pointless unless you want to be judged against the performance of seven mega-caps you might not want to own.”

However, concentration and indexing flows can, over time, open up opportunities for stockpickers who look elsewhere, Credo director Rupert Silver said, meaning that the continued rise of passive investment will eventually create such clustering of ownership that “active managers will find outperformance easier when hunting away from the crowds”.

However, he does not believe markets have reached that stage yet.

History rhymes

Evan-Cook sees parallels with earlier periods of extreme enthusiasm.

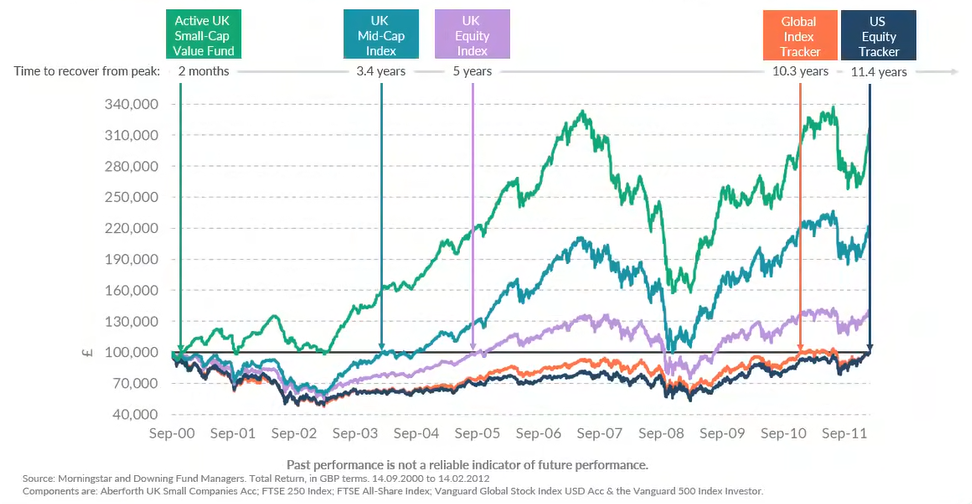

“I certainly would not put my own money in the S&P 500 today, at least the market-weighted version, because it's too heavily dominated by too few names,” he said. “It does remind me a lot of 1999/2000 and that turned out to be a terrible time to buy. It took about 11 years from its peak before you broke even as a UK investor.”

This is shown in the dark blue line in the chart below.

Repercussions of the 2000s equity breakdown

Evan-Cook also sees similarities with the Nifty Fifty era, where dominant companies were treated as untouchable until valuations eventually unwound. Even the equally weighted index only partly addresses the issue, because it still concentrates exposure in large companies at a time when he sees better prospects in small- and mid-caps outside the US.

“Most investors probably don't need to have that exposure, unless they're a fund manager trying to protect their career.”

The counterargument: Quality, dominance and the risk of staying out

No one said the S&P has become completely uninvestable, however, with Silver noting that the companies at the top of the index justify much of their weight.

“Whilst the index has become more concentrated and therefore more correlated with technology (and we do recognise there is a speculative element in the market), the largest weights in the index belong to some of the most extraordinary businesses the world has ever seen,” he said.

“These companies often exhibit wide moats, exceptional growth, high margins, network effects and significant balance sheet strength. They represent the tech revolution in America and ignoring them purely on valuation grounds has been a mistake historically and may well prove so in the future.”

What it means for investors

How investors should respond to this lies in the practical choices in asset allocation. These include whether to underweight the S&P after years of extraordinary outperformance; whether an equally weighted approach offers a more balanced exposure (and the issues it throws up in portfolios); how far global diversification can mitigate concentration risk; and how time horizon shapes all of these decisions.

Too many investors have not yet caught up with the reality of the index, with “everyone doing exactly the opposite currently [of what they should], and charging towards that,” Evan-Cook concluded.