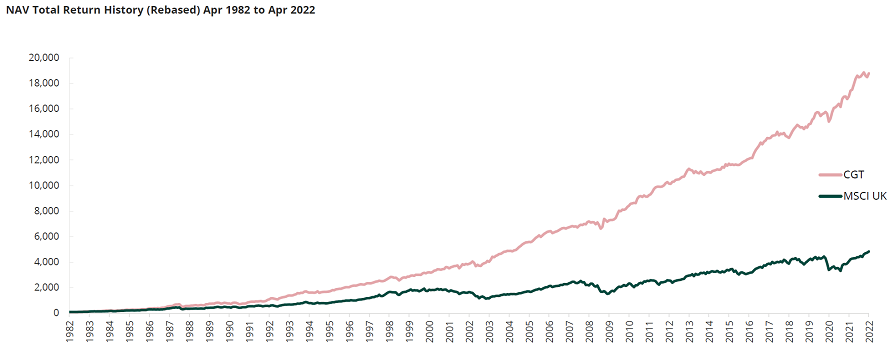

Even more impressive is that he has managed to deliver these returns with significantly less volatility than the UK stock market, losing money in just one of the 40 financial years he has been running the trust.

Source: Capital Gearing Trust

Yet he admitted he hasn’t got everything right over this time, and for a manager whose priority is “to not lose money”, what he regards as his biggest mistake may come as a surprise.

“Post the financial crisis, the one thing that I now appreciate was the extent to which if the Fed supplied liquidity in unlimited quantities, essentially that was going to drive up the price of financial assets to way beyond fair value,” he said.

“I'm always instinctively a seller at above fair value, but I think I should have appreciated that in those special circumstances, where we had monetary policy which was accommodative to a such a degree, you were going to get asset bubbles. In hindsight, perhaps it was foolish not to participate in them.

“But I didn't want to be in them at the point where they started to collapse, and we always thought that they probably would.”

Capital Gearing Trust currently only has about 15% of its portfolio in equities. The biggest weighting is to index-linked bonds, at about a third of assets, due to Spiller’s view that the market is underestimating the threat of inflation in the short to medium term.

In a previous note to investors, he said many deflationary forces that emerged in the 1980s and 1990s such as globalisation and the internet were now declining in power, or even being rolled back.

And while interest rates have already been raised, he said that won’t get anywhere near the level needed to bring inflation under control.

“All the way through the first half of the 1970s, focus groups showed that what voters cared about was employment, and as long as this was fine, they would vote for the incumbent,” Spiller explained. “They didn't like inflation, but it was a secondary threat.

“By the time we got to the end of the 1970s, inflation was public enemy number one. And the electorate would vote for policies that were draconian to defeat inflation, even if it meant there was a recession.

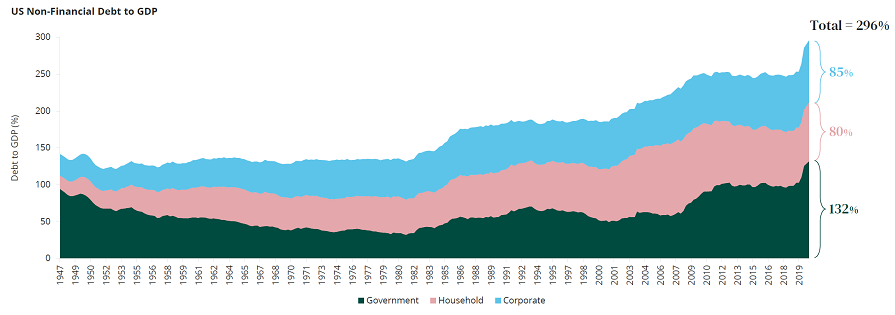

“But the point of all this is that today, balance sheets are not in great shape, so a recession runs a significant danger of turning into something worse and repeating the mistakes of 1929 and 1930.”

A graph of combined government, household and non-financial corporate debt to GDP in the US shows this figure is currently at 296%, more than twice its level at the start of the 1970s.

Source: Source: Bank for International Settlements, numbers do not add due to rounding

Spiller has not always been so pessimistic: in the 1980s, he put more than 90% of the portfolio in equities and used debt – such as through holding investment trusts and gearing the trust’s balance sheet – to supercharge the gains from the stock market.

While interest on the debt was as high as 11.5% back then, this still proved to be the right call.

“If valuations are low, then risk is low even if volatility is high and vice versa,” Spiller explained.

“Paradoxically, the best time to borrow may well be when interest rates are very high. Investors attracted by very low interests rates have often leveraged their assets, in the process raising asset prices and reducing the returns available.”

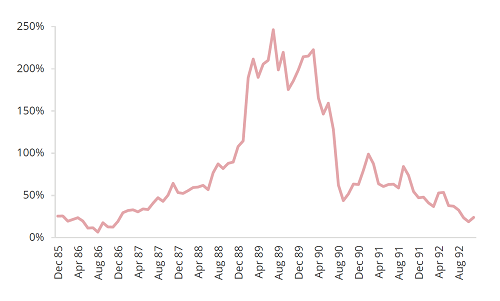

One side effect of the Capital Gearing Trust’s strong performance in the 1980s and the way this was reported was that its premium surged. Regulations at the time prevented the issuance of new shares where the directors could not identify who was buying them, meaning they had little control over the price to NAV.

This resulted in one investor buying the trust at a premium of 250% in the late 1980s.

“Whilst they were very poorly advised in their actions, if they still hold their shares today, they have outperformed the UK stock market,” Spiller said, adding that investment trust directors “should make much greater use of their hard-won powers of discount control”.

Share price to NAV 1985 to 1992

Source: Capital Gearing Trust

Overall though, he has been happy with the trust’s board over the years, pointing out its story could have been cut short as early as 1985 had the directors not rebuffed a hostile takeover bid from a stockbroking firm called Harvard Securities.

This proved to be a good call, with the trust’s co-manager Chris Clothier noting that Harvard turned out to be run by “bona fide crooks”.

In 2014, Tom Wilmot, who was Harvard’s chairman and chief executive before its collapse, was charged along with his two sons for boiler room fraud perpetrated against 1,700 investors.

“I think they're out of prison now,” Clothier added. “[Wilmot] appeared in court rather scruffily and apologised to the judge, saying that his now ex-wife had burnt all his clothes. Perhaps that’s all you need to know about the character of the individual.”

At the age of 73, Spiller said it is only natural he gets asked about succession planning. He said one of his proudest achievements over the past 40 years is that he has put together a team that would improve the performance of the trust if he retired tomorrow.

“The important thing is that Alastair [Laing] is CEO,” he added. “And the point is that there is someone who can tap me on the shoulder and say, ‘you know what Peter, you used to be good’.”

Capital Gearing has ongoing charges of 0.58% and is on a premium of 1.3%.