Nick Train was a “gun-slinging trader” at the start of his career but a book by John Train on renowned US investor Warren Buffett shaped his philosophy to what it is today, the manager has revealed.

Talking on The Value Perspectives podcast last week, one of the UK’s most popular fund managers said he “shudders” when thinking about the start of his career – and the performance he was delivering for investors.

In the early years, “you are experimenting with other people’s precious savings,” the WS Lindsell Train UK Equity manager admitted, as he was trying to find his way in the industry.

“I was dissatisfied – probably with my performance at that time. [I was] certainly, intellectually and emotionally dissatisfied with the way I was attempting to do it. I guess you could say I was trying to be a gun-slinging trader, like everybody around me was. But it wasn’t working.”

Around four years into his career the FE fundinfo Alpha Manager read John Train’s book, which he said “had a profound effect and subsequent influence” on how he runs money today.

“I reckon you could almost look at a chart of my performance and see the inflexion point where I read that book and thought, I need to start behaving and running money this way,” he said.

One of the immediate changes was to reduce the number of individual investments, bringing down his trading activity, and to stop thinking of stocks as “trading chips”.

“I needed to start thinking about equities as though they were irredeemable gilts with a variable coupon – but the coupon had a bias to go up over time,” he said. To do this, considering long-term cashflow was “helpful” to get out of the “trading mindset”, he added.

Train went on to launch his eponymous asset management firm Lindsell Train, alongside Michael Lindsell, in 2000.

He set up the firm because he was dissatisfied with the way he and Lindsell were told to run money at larger institutions. These “institutional imperatives” meant he was asked to invest in a way that was at odds with how he now believed he needed to invest.

“The institutional imperatives where Mike Lindsell and I were working were impinging on the way we would have chosen to allocate our own savings. And that divergence between what I was being required to do as a professional and what I wanted to do as a private investor was untenable,” he said.

Train added this remains a concern for him today when viewing the next crop of investment managers coming through. He is worried this can discourage “younger, talented investment managers” from taking the necessary risks to generate strong active returns.

“Maybe it’s not going to work, but you’ve got to try – you owe it to yourself and to your clients to try,” he said.

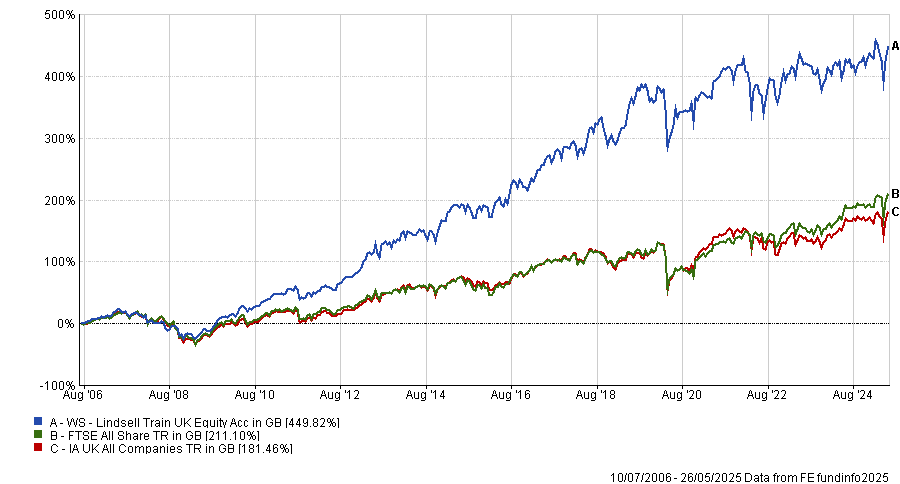

It would be hard to define his decision to go it alone and try for himself as anything other than a success. Train is the sole listed manager on the £2.3bn UK equity fund, which has made 449.8% since its inception in 2006 – the third best return in the IA UK All Companies sector.

Performance of fund vs sector and benchmark since launch

Source: FE Analytics

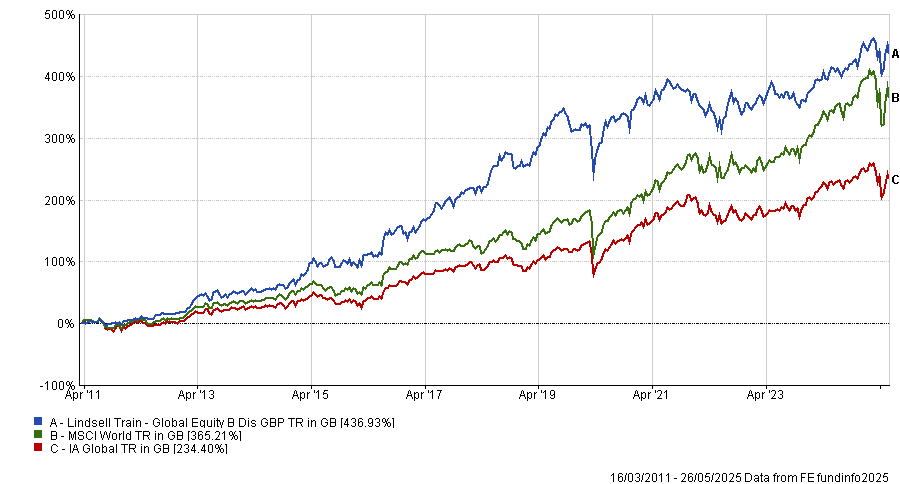

Meanwhile, the £3.8bn Lindsell Train Global Equity fund, which he launched with Lindsell in 2011, has been the eighth best performer in the IA Global sector since inception, making 436.9%.

Performance of fund vs sector and benchmark since launch

Source: FE Analytics

Performance has dipped more recently – both funds sit in the bottom quartile of their respective peer groups over five years, with the UK fund in the third quartile over one and three years as well. The global fund has picked up more recently, however, beating the average peer over one and three years.

This underperformance has weighed so heavily on the manager that he admitted: “If my last three years’ performance had been the first three years at Lindsell Train, we wouldn’t have a business”.

He said that investment managers can get “some credit in the bank” from past performance, depending on how well their investment approach has worked, adding that he has been “lucky” that at “telling moments” his fund has performed well.

The Alpha Manager attributed this to investing over long time horizons. This means the portfolio may perform well in the short term, but is not something that is controlled.

There are patterns, however. For example, he noted his strongest periods of relative performance seem to be associated with periods when “everything is going right”.

“It’s not deliberate” he observed, adding that he is now “humble in the face of markets” – even more so now after the past few years. A far cry from his gun-slinging early days.