Banning the now-former president of the US from Twitter might have come as a relief for some, but not for Jack Dorsey, the founder and chief executive of Twitter itself. In a series of posts, he as much as acknowledged that the move could be a watershed moment for the industry.

“Let’s just break them up”

Breaking ‘Big Tech’ up looks deceptively easy, especially as support is increasingly bipartisan. After all, if the US government could defeat a John D Rockefeller, millennial Mark Zuckerberg looks like less of a problem. And, given the proven impact on electoral behaviour, one can see why the government would be keen to be rid of such influence which has already significantly disrupted the status quo. But the implications for everyone, markets included, make matters very complicated.

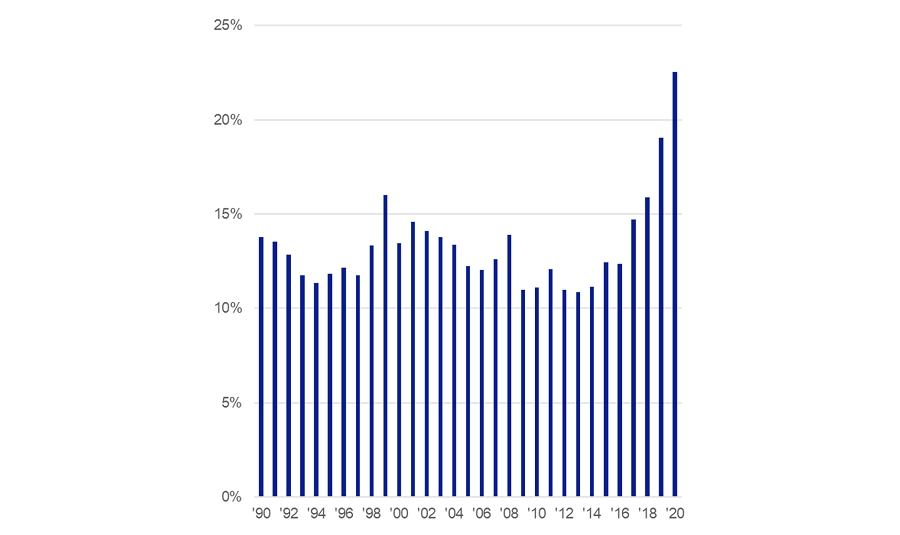

Let’s start with the obvious. The top-five US tech companies (Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft, Google-parent Alphabet and Apple) account for almost 23 per cent of the S&P 500, almost double the concentration of 10 years ago.

S&P 500 top-five concentration

Source: Mazars

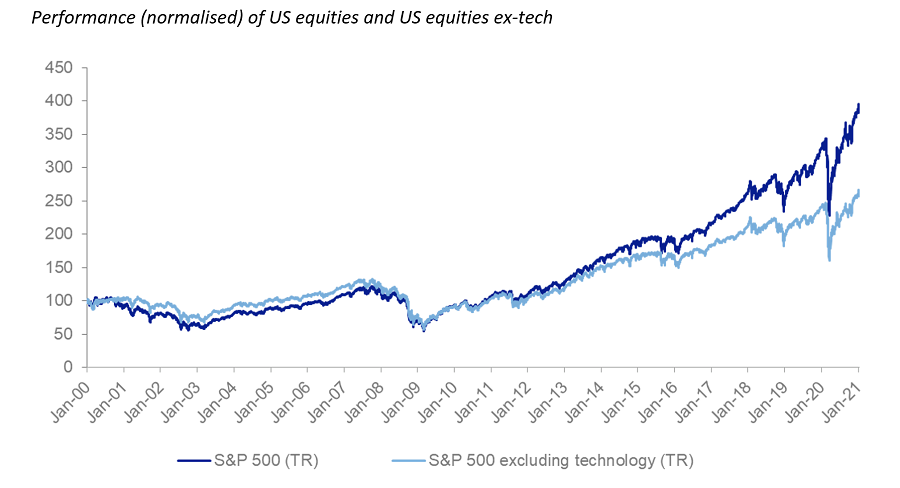

Breaking them up could have significant consequences for the world’s leading equity index, as much as the retreat of banks had 12 years ago. Performance leadership also belongs to those companies.

Performance (normalised) of US equities and US equities ex-tech

Source: Mazars

Currently, investors know the business models and trust the leaderships involved. Will they be as open to investing in the tens of companies, all run differently by different people, that will come as a result of the break-up? Also, given the low entry barriers to the industry (building a social media platform is much cheaper than building a steel plant), could that mean the end of those companies altogether?

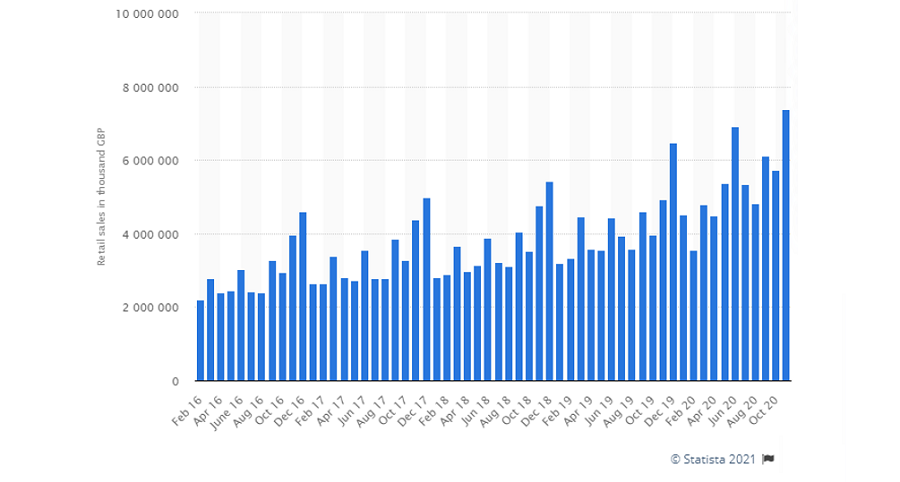

And then there’s the question of the wider economic impact. Not so much in terms of people employed in tech, but in terms of the millions of businesses which rely on Google, Apple, Amazon, Instagram, Facebook and Twitter for their survival and expansion. In 2017 it was calculated that 90 per cent of US businesses were using social media for marketing purposes. In the UK alone, migration to off-store sales has been spectacular in the past few years.

UK Non Store Sales

Businesses which have spent billions building viable marketing models on social media are in danger of seeing their long-time efforts and investment lost in an instant. The power of tech is not in its tangible assets, like the monopolies of the 19th century, but rather on the large number of people and other businesses who depend on them. Will consumers embrace their successors the same? Will they want to deal with 10 platforms where they only had one? Won’t concentration just happen again in the next successful platform?

For better or for worse, we live in an internet world with Big Tech at the very centre. Breaking it up would have unpredictable far-reaching consequences. Not breaking it up could keep electorates on the path of extreme polarisation and hyper-partisanship we witnessed in the last few years, with disruptive long-term effects for democracy.

In a last-ditch effort to avoid legal action, social media has tried to demonstrate an ability to self-regulate, by blanket-banning the President of the United States. However, we are probably past that point. Self-regulation is, in reality, a reaction before the state steps in, which it does when it’s both politically palatable and expedient, i.e. after industry failures made visible in the public sphere compel those who hold political office to act. Historically, no dominant industry has ever successfully self-regulated: 19th century electricity, oil, steel and trains were broken up; and, 20th century oil was heavily regulated after accidents like the Exxon Valdez or Deepwater Horizon. Banks were only the latest case of a dominant sector where self-regulation failed, forcing the state to nationalise and then monitor most of their activities.

An alternative to break-ups

While regulation seems inevitable, we believe that “breaking” companies may not necessarily be the endgame and that a lot of thinking will be required in solving this particular conundrum. Facebook (which also owns Instagram) is not Standard Oil Co 120 years ago. It is much more global, accessible and interconnected. The number of stakeholder companies which rely on it amount to millions. A lot of them are smaller enterprises which have found a way to advertise and compete without having to pay expensive advertising agency fees. Some 77 per cent of US small businesses use social media for key business functions. Reducing social media efficacy could significantly increase industry concentration, especially in the wake of Covid-19 which already sees a lot of smaller companies scrapping for cash. Even more importantly, ownership of Facebook, Twitter, Google, Apple and Amazon is significantly more public for shareholders whose pension accounts would stand to lose.

But 21st-century problems require 21st-century solutions. One solution proposed is a universal clampdown on social media, by accepting a more centralised and regulated internet architecture, like the one China’s Huawei proposed over a year ago.

Another, practically more difficult but demonstrably more liberal approach would be to try and regulate the proprietary – and secret – algorithms which filter and direct content. At the core of modern communications technology is “ever efficient product targeting”. While they facilitate sales, it is hard for the algos to discern between a consumer who might be looking to buy a new laptop after having searched for a battery for his old one, and a citizen on the verge of political radicalisation.

The sheer speed at which filter “bubbles” develop is often reminiscent of “High Pressure” sales tactics, which have already been regulated away in many industries like finance. And the persistence of the bubbles generates behaviour not unlike the one American psychologist Leon Festinger described in religious cults. It would cost social media companies some money to fix this, but they could allow for more diverse information to infiltrate the “bubble”, to reduce some of the worst aspects of social media addiction.

What is important for investors is that neither scenario is catastrophic for their holdings. Both simply bring valuations closer to average and might not be as hugely disruptive for the world economy as are break-ups.

Banning Trump was not the end of populism, which is constantly fuelled by stagnating incomes in the west and only fanned by the awesome power of social media. It might prove, in the near future, to have been the first salvo of the 21st century ‘Tech Wars’. The choices are difficult. But the outcome will affect markets, investors and the real economy in ways we have yet to understand.

George Lagarias is chief economist at Mazars. The views expressed above are his own and should not be taken as investment advice.