De-industrialisation is defined as the progressive closure or downsizing of manufacturing industries in a place, city, or region. An emotive word that can conjure up job losses, lower living standards and irreversible decline.

In the UK, the industrial past holds a particularly heavy weight on the psyche. Coal, shipbuilding, textiles – the scars of their decline linger, and with them the sense of fear that it will happen again.

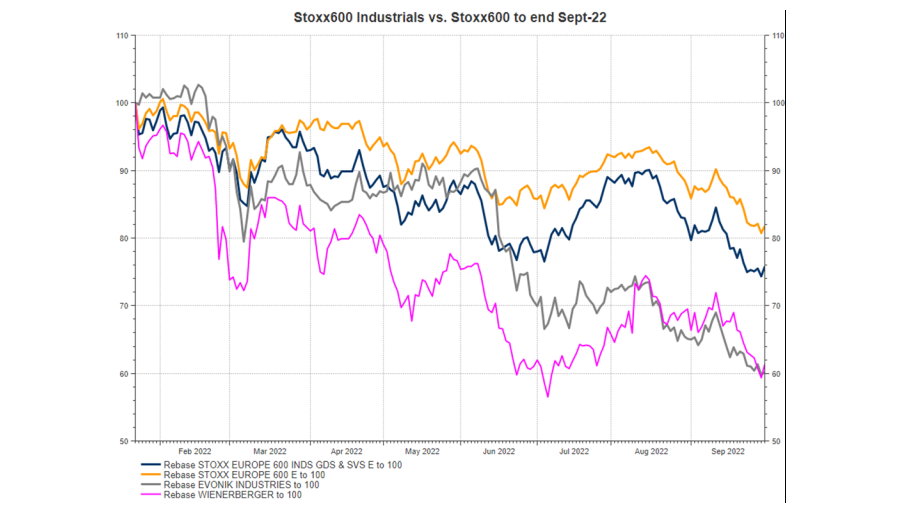

That was the kind of fear that came to torment Europe in late 2022. As gas prices jumped, markets did what they do best: panic.

In late September, a Goldman Sachs chemicals research note carried the headline ‘Deindustrialisation of Europe could be a 1.6 trillion tail risk’, with an estimated 40% of European chemical output at risk of permanent closure.

The concern became contagious. Small and medium businesses and supply chains would get caught up in the aftermath. Was this a re-run of the Eurozone debt crisis? For the share prices of exposed industrial and chemical companies it was a case of shoot now, ask questions later.

Source: Refinitiv Datastream, Jan 2023

But the world has a habit of showing how poor we can be at predictions. Economies and industries are ecosystems, not spreadsheets.

Then there is an unwritten law that often gets forgotten: when profitability comes under threat, capitalism gets a kick up the backside. Just as was the case during Covid, billions of people are incentivised to wake up every day to find ways of adapting. A new vaccine was ready in just under a year versus the usual 10+ year timeframe.

Last summer, Germany started work on its first liquified natural gas (LNG) import terminal, in Wilhelmshaven, a project that would normally be expected to take five years. It was opened mid-December and took its first full cargo a few weeks ago.

In another sign that the cure to high prices is high prices, German chemicals producer Evonik managed to replace the equivalent natural gas usage of 100,000 households by engineering an liquified petroleum gas (LPG) tie up to a nearby BP refinery. Was that in anyone’s model?

High prices remain a force for inventiveness and we can see this, for example, with heat pumps. The roll out of residential heat pumps is well publicised but behind the scenes Europe is also moving fast on larger scale applications.

After a successful trial that saved just under half a million euros in energy costs, Austrian brick manufacturer Wienerberger is rolling out the technology to other brick foundries across the continent.

Defining and measuring the ‘manufacturing’ sector has become problematic as industrial value chains have become deeply integrated into service and technology offerings.

Europe’s leading companies were never leaders because of an energy cost advantage and they have long had to compete with lower cost competition from overseas. Many chose to become more specialised, which increased margins and often reduced cyclicality.

By embracing demanding regulatory and quality standards, some European industrials have thrived on the global stage. Schneider Electric for one, has completely redesigned its operations, tying together products, services, and software to bring efficiency to buildings, factories, homes and infrastructure.

European revenues made up 44% of the total in 2008, but today that figure is 26%. It could even rise again, as the strategic preference for nearshoring takes hold. Taking a leaf out of Amazon’s book, Schneider has taken learnings from its own environmental performance and created an entire service offering around sustainability consulting.

These examples are not supposed to offer proof that cyclical downturns are either unlikely or inconsequential. Instead, they try to explore a wider set of actions, reactions and outcomes.

When realising that exact answers cannot be arrived at, and are therefore not worth pursuing, share prices can be turned into useful hurdle rates that imply reasonable or unreasonable scenarios.

We can’t, and thankfully don’t need, to know what Europe’s GDP growth will be in 2023. While determining ‘what is in the price’ is not a perfect science either, the problem is simplified by betting on only two things.

First, that the cycle of market fear will always oscillate between overly optimistic and overly pessimistic and secondly, that the purpose of any industrial company worth investing in is to constantly optimise solving problems. These cycles of fear are gifts in the form of future returns.

Alasdair Birch is an investment manager at Saracen Fund Managers. The views expressed above should not be taken as investment advice.