Despite bouts of volatility, the past 15 years have generally been favourable for asset prices. For much of this time, both equity and bond markets have delivered strong returns for investors, helped by a tailwind of supportive monetary policy from central banks. That has meant that owning ‘the market’ has generally been a winning investment strategy, and it came with the bonus that it was typically a cheap one at that.

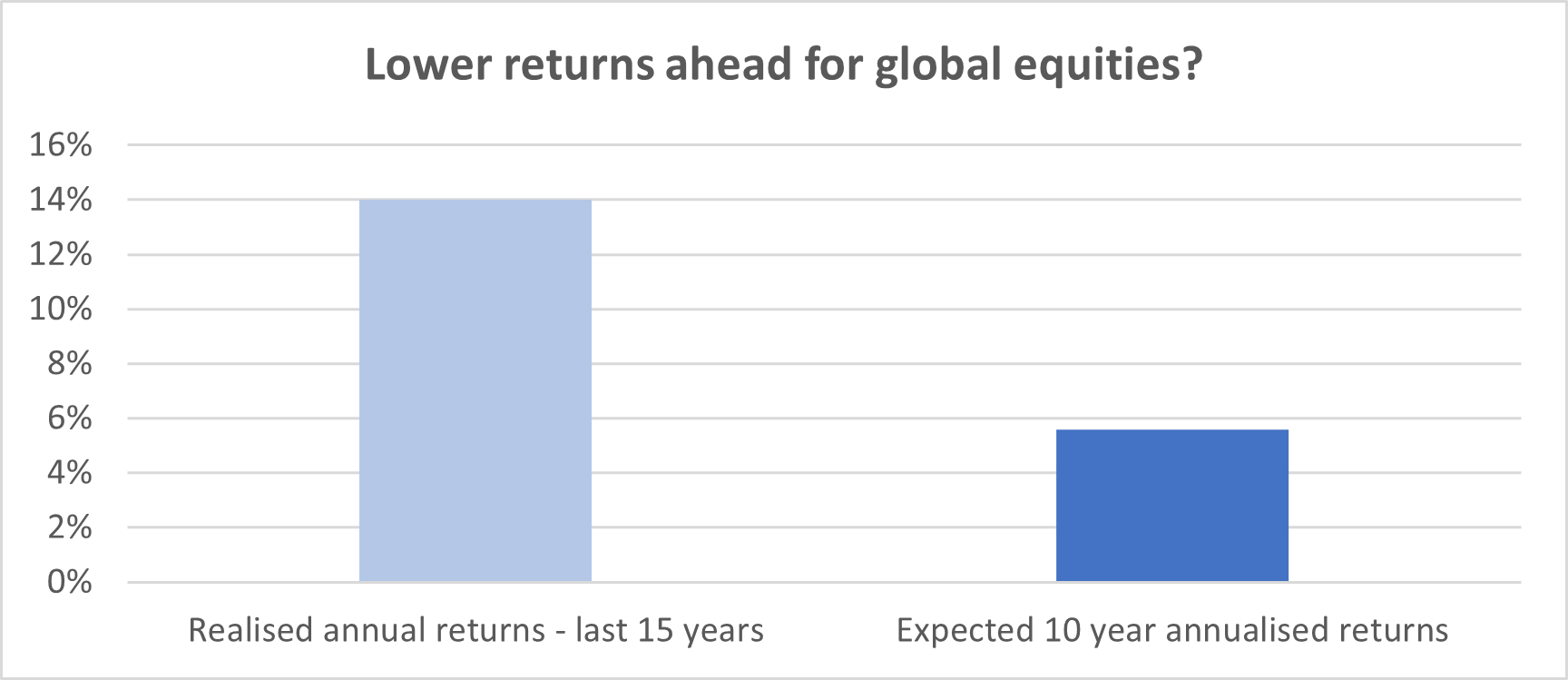

To put this into perspective, an MSCI All Country World Index (ACWI) exchange-traded fund (ETF) is likely to have delivered around 14% annualised in sterling terms since the low of the global financial crisis in March 2009. That’s well above the long-term average return of global equities.

A balanced investor would also have done well by owning the market – for example, a 60/40 portfolio (60% MSCI ACWI exposure and 40% Bloomberg Global Aggregate Bond exposure) would have delivered something like 10% annualised in sterling terms.

Investors could essentially ‘set and forget’ their asset allocation over this period and experience strong returns at low cost; what’s not to like?

I would argue that the next 15 years are unlikely to be like the past decade and a half for financial markets. And there are several reasons why.

A more challenging return environment ahead?

Firstly, the high valuations of global equities today are likely to be a headwind to future returns. In the short-term, valuation isn’t necessarily a great predictor of future returns, but over the long-term, it is a very powerful one. High starting valuations do not tend to augur well for future returns. In other words, the 14% annualised return experienced by global equity investors over the past 15 years is unlikely to be repeated.

What can we expect instead? It is of course a fool’s errand to try to predict what specific returns will be, but we can get an idea of potential magnitude. For instance, Invesco’s capital market assumptions (CMAs) indicate a much lower annualised return for global equities (MSCI ACWI) of around 6% annualised over the coming years. If this turns out to be even close to correct, then it is fair to question whether owning ‘the market’ will deliver enough for investors.

Sources: Bloomberg and Invesco. Realised returns – past 15 years are total annualised returns in sterling terms for MSCI ACWI as at 30 Apr 2024. Expected 10-year annualised returns are nominal return estimates based on Invesco’s 10-year capital market assumptions.

How diversified is the market?

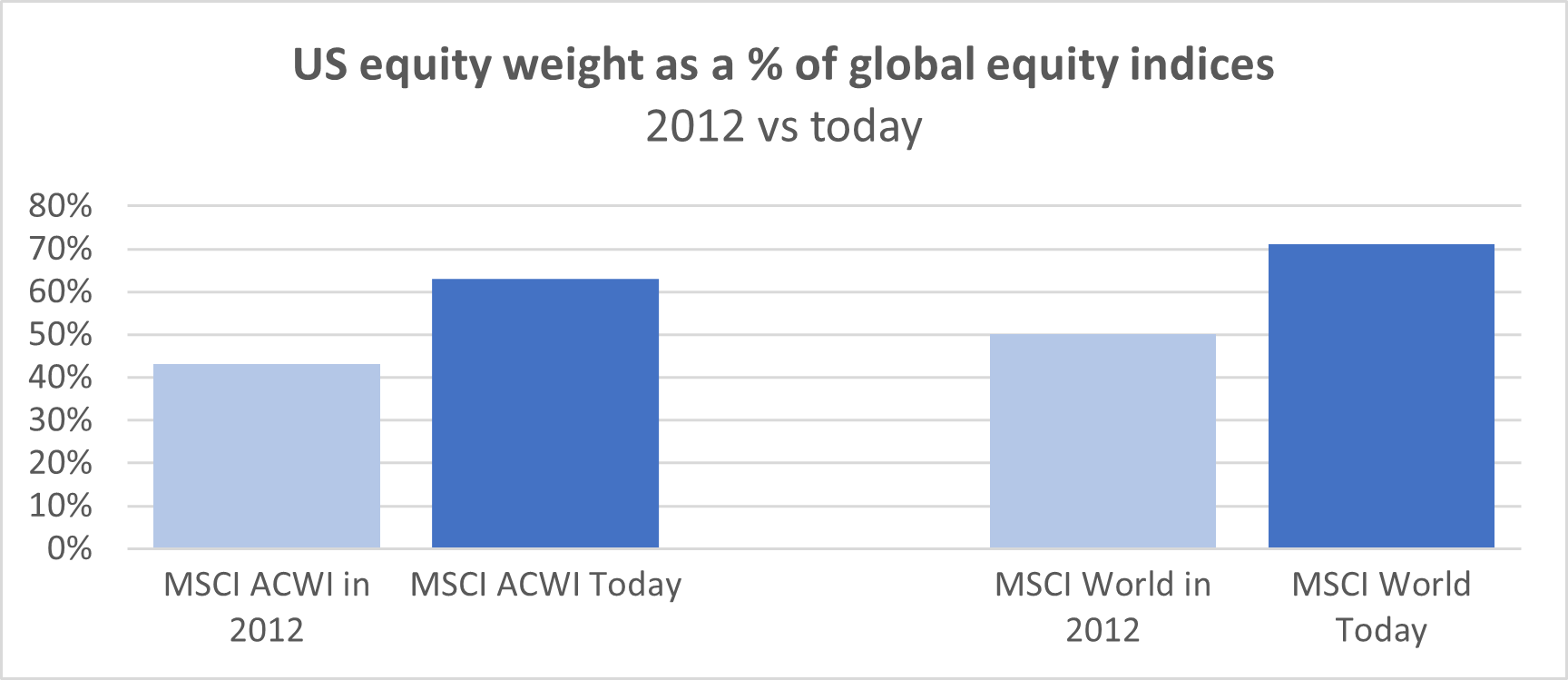

Second, markets have in some cases become more concentrated and skewed over the past 15 years. US equities are a glaring example of this and they are a big part of the reason that the overall market looks expensive.

When I joined Invesco in early 2012, US equities made up around 43% of MSCI ACWI and around 50% of MSCI World, the former being the ‘all countries’ index and the latter being ‘developed countries’ only.

Source: MSCI as at 30 Apr 2024

Today, US equities account for around 63% and 71% respectively. Essentially around two-thirds of global equity exposure is US exposure. That is a lot of reliance on one market, especially one which is trading at what appear to be lofty valuations.

Currently, the US equity market’s 12 month forward price-to-earnings ratio is around 30% above its longer-term average.

While it may seem that the US has always outperformed, it’s worth remembering that this isn’t always the case. For example, in the first decade of the 2000s, US equities significantly underperformed the rest of the world, particularly emerging markets.

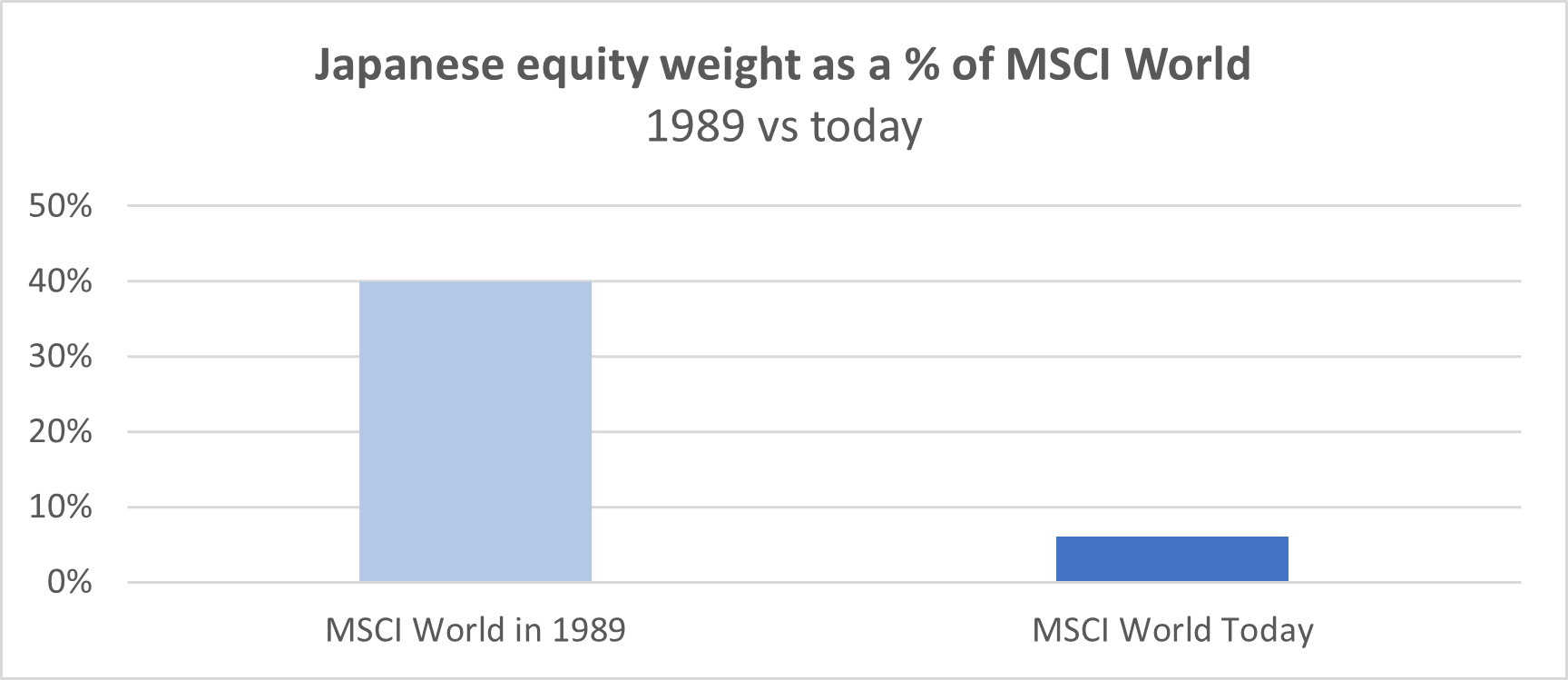

Japan is an interesting – albeit extreme – historical example of what can happen when markets become too prominent or concentrated. By 1989, Japanese equities had performed strongly and came to dominate the global market, accounting for around 40% of MSCI World. What followed was a multi-year period of underperformance and an exodus of investors. Today Japanese equities account for just 6% of MSCI World.

Source: MSCI as at 30 Apr 2024

A more challenging future means a more flexible approach

Given the risks of a more uncertain environment, lower market returns and a potential lack of diversification, what are investors to do?

I think a more flexible approach is a must. In my view, having two-thirds of the equity exposure of a ‘global’ portfolio in one single country is a significant risk. The ability to adjust asset allocation over time will therefore be an important tool in the investor’s toolkit in the coming years. As will the ability to change the underlying funds and ETFs they may invest in to ensure that no unintended biases are present in portfolios.

In short, take a more active approach, even if that is done by using passive underlying investments.

For those who would rather somebody else make those active asset allocation decisions on their behalf, the good news is that the cost of active management has reduced dramatically over the past 15 years. It is possible to access active asset allocation for relatively low cost. Over the next few years, I think that will prove to be a price worth paying.

David Aujla is a multi-asset strategies fund manager at Invesco. The views expressed above should not be taken as investment advice.