A drop in markets during the first year of retirement can cut the long-term value of a pension pot by tens of thousands of pounds, according to new modelling from RBC Brewin Dolphin.

Retirement marks the point when people shift from saving money to drawing an income from their savings. This phase – known as decumulation – makes the timing of investment returns especially important. If markets fall early on, ongoing withdrawals can make losses worse and shrink the pot faster than expected.

This type of risk is different from the ups and downs investors may see while building their savings. Even when long-term returns look healthy, early losses can have a lasting impact on how long retirement savings will last.

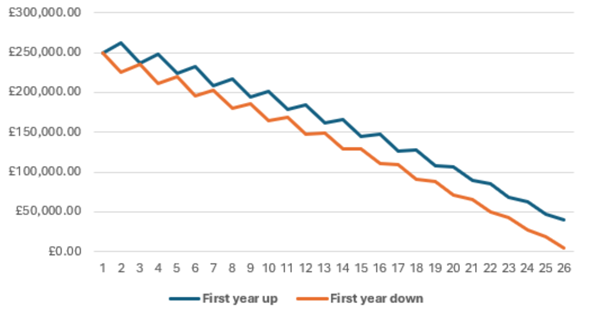

To explore this, RBC Brewin Dolphin looked at a scenario where markets rise by 10% one year and fall by 5% the next, repeating that cycle over 25 years. They assumed a steady annual withdrawal of 5% from the starting pot and an average annual return of 5.23% after fees.

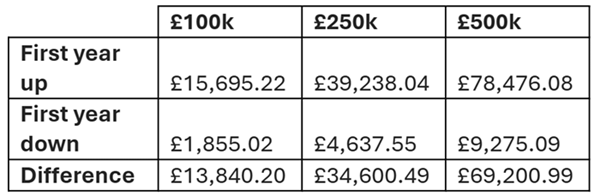

In one version of the model, a retiree with a £250,000 pension pot who withdraws £12,500 a year would still have £39,238 left after 25 years – but only if the first year saw a 10% market rise. If the first year brought a 5% decline instead, the pot would shrink to just £4,637. That £34,600 difference is equal to more than two years’ worth of withdrawals.

What’s left after 25 years of 5% withdrawals from retirement pots

Source: RBC Brewin Dolphin

This is what RBC Brewin Dolphin refers to as “pound-cost ravaging”, or the damage caused by pulling money from investments during a market downturn.

Rob Burgeman, a wealth manager at RBC Brewin Dolphin, said: “Most people will have heard about the benefits of pound-cost averaging – investing over time to take the edge off market volatility and gradually build wealth.

“What they may be less familiar with is pound-cost ‘ravaging’, which demonstrates how taking money out at the wrong times can have a big impact on your retirement pot in the long term.”

This pattern holds across different pot sizes. Someone with £100,000 would be left with £15,695 if markets rose in year one, or just £1,855 if they fell. For a £500,000 pot, the difference is even starker: £78,476 compared to £9,275, a gap of £69,200.

Withdrawing £12,500 from a £250,000 retirement pot over 25 years

Source: RBC Brewin Dolphin

Burgeman said that even when long-term average returns stay the same, early market losses can leave people short. “If markets fall in the first year, it can create a hole in your retirement plan that only grows over time,” he said.

“But that example is merely illustrative of a much wider point – if the value of your investments declines over an extended period, the effects will be amplified because you have to sell more of your assets to maintain your withdrawal amount. And that runs the risk of leaving you short towards the end of retirement.”

The model uses simple assumptions, but the underlying risk (which is known as ‘sequence of returns risk’) is well known. It describes how the order in which investment gains and losses occur can affect the outcome when withdrawals are being made regularly.

“Markets do not move in straight lines. A bad first couple of years can make all the difference, which people retiring in 2007 or 2019 may have been unfortunate enough to find out,” said Burgeman.

“And if you had retired in 1999, the three-year bear market that followed may have scuppered your plans altogether. Once retired, market conditions become really important to you and the adage about time in the market is still important, but has a different relevance.”

To manage these risks, Burgeman said retirees should build flexibility into their financial plans. “Scenarios like this are why having a financial plan, and taking professional advice, can make a significant difference to your retirement,” he finished.

“This will allow you to take steps, such as keeping a year or two of cash aside, to build in flexibility and avoid making withdrawals when markets are down, ensuring your savings last as long as they possibly can.”