Equities “may no longer be the answer” for long-term investors, according to Ruffer’s Duncan MacInnes, who warns high starting valuations and a likely sea change in society following the coronavirus pandemic mean they are not the one-way bet they are often assumed to be.

The co-manager of the Ruffer Investment Company is not diametrically opposed to equities, referring to them as “possibly the best wealth-creating asset on the planet over the long term”.

However, he said the problem with this statement is the vague nature of the phrase “long term”.

“Remember, we don’t always have the long run, unless you’re a perpetual endowment charity,” he explained.

“The rest of us all have one run and that one run is usually 20 years or so.

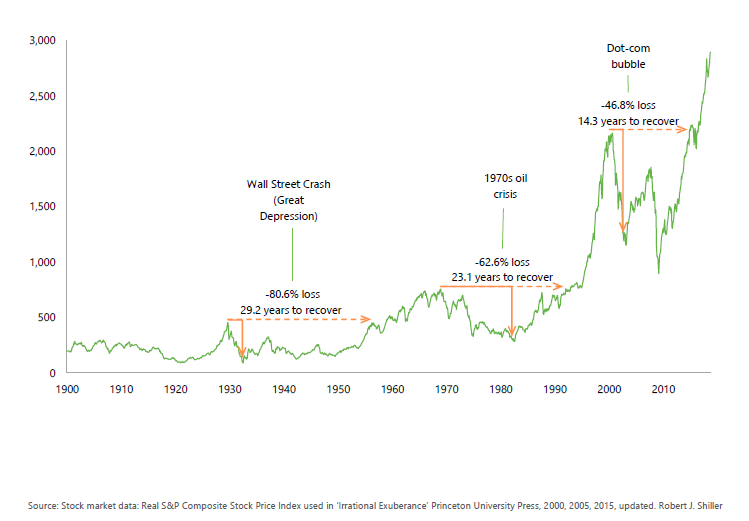

“There have been long periods where equity markets have travelled nowhere in real and nominal terms. Picking out a few examples, buyers in 1929 lost 80 per cent of their money and had to wait 30 years to get back to breakeven after inflation. In 1969 or 2000, they had to wait 23 years and 14 years, respectively. These are lost decades. But they are also lost opportunities to compound your wealth.”

"Lost decades" in US market

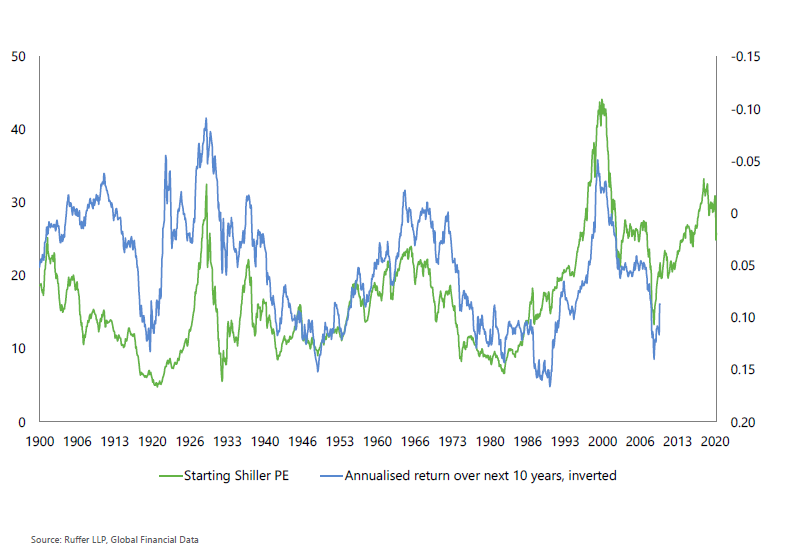

MacInnes said a reliable signal that you are staring down the barrel of a “lost decade” should be obvious, but is often overlooked: a high starting valuation. Pointing to a chart of starting cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratios and 10-year returns, he said that on the market’s current P/E (price-to-earnings multiple) of 25x, investors can expect average gains of 2.5 per cent a year over the next decade – and this is before inflation.

Starting valuations and 10yr returns

“A pretty sobering thought,” he added.

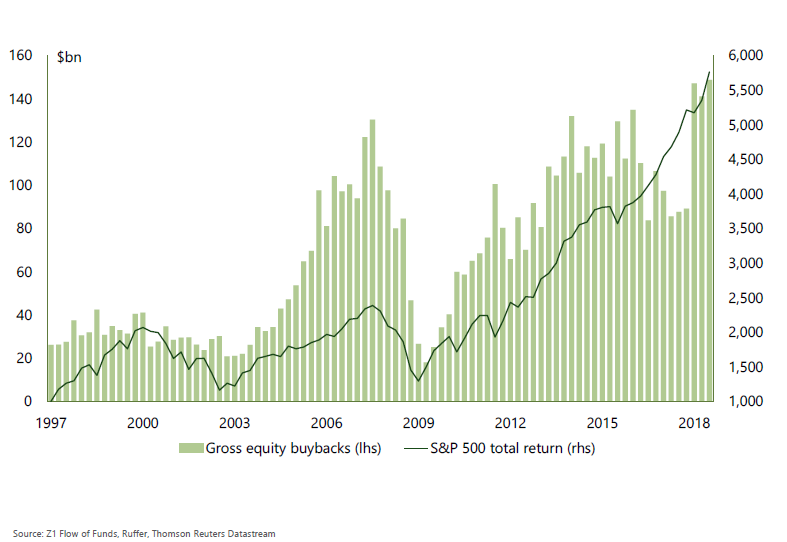

And the manager said that one of the main tools used to propel share prices ever higher over the last decade now looks set to be severely limited.

Since 2009, US corporates were the single biggest buyers of equities in the market, even ahead of institutional investors. Share buybacks accounted for more than $5trn in the past decade, with this figure accelerating to just below $1trn a year in the final stages of the bull run.

Share buybacks and total return

“You probably know the playbook that these companies were following: borrow money cheaply in the bond market and use the proceeds to buy back your own stock, which makes your earnings per share better which, all other things being equal, helps the share price go up,” MacInnes continued.

“From here, I think for at least 2020 and maybe 2021 as well, we expect buybacks to be vastly reduced and therefore that lack of support for the market is likely to disappear.

“Buybacks have acted as a contra indicator, because companies have a horrible track record of buying back much more stock at the top, when spirits are high and prices are elevated, and much less at the bottom, when their stock price is actually much cheaper, and the buybacks would be more effective. And the consequence of that is they destroy shareholder capital.”

MacInnes said the most egregious example of this could be seen in US airlines. Over the past five years, the sector levered up and spent $45bn on share buybacks, cheered on by hedge funds.

The handful of CEOs responsible for this financial engineering pocketed $400m between them.

“But then the virus struck,” the manager continued, “and they had to go cap in hand to the government for bailouts and needed to raise equity from shareholders at much lower share prices than what they were originally buying back stock for before the virus.”

“This game is over now, because buybacks, dividends and mergers and acquisitions have become particularly toxic.

“Along with beating on China, bashing buybacks is one of the few issues that has support of the left and the right of the political spectrum: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Liz Warren, Bernie Sanders – even arch-capitalist Donald Trump senses the populist needs and is chipping in against buybacks.”

Buybacks are just one example of corporate excess seen in various industries that MacInnes believes will lead to a pushback from the electorate and a change in corporate behaviour – away from “shareholder primacy” and towards stakeholder capitalism, where more emphasis is placed on what is best for employees and society as a whole.

He said this can best be summed up as “from just in time to just in case”, with businesses holding more inventory, shortening supply chains, reshoring manufacturing and running with less debt.

Unfortunately, he pointed out the one thing that all of these trends have in common is they are bad for margins.

So how can investors navigate this environment? Ruffer’s investment director Bertie Dannatt previously spoke about his expectations for a spike in inflation in the coming years, and as a result the highest exposure in the trust is to inflation-linked bonds.

For those who are set on equities, MacInnes said one option is to invest in businesses that have a head-start on stakeholder capitalism, such as in Japan where there is low inequality compared with the rest of the world and balance sheets are “rock solid”.

Another is to invest in companies that offer a solution to society’s problems, and the manager pointed out you don’t need to travel to the other side of the world to find examples of these.

“Tesco is rising from the ashes like a phoenix and becoming a national champion again,” he said.

“It was previously a company to be proud of, before it had several missteps in the middle of the last decade. But during this pandemic, it has kept the nation fed, it hired 45,000 workers when everyone else has been laying them off, it sent vulnerable workers home on full pay and it fully funded the pension fund when it sold the Asian business.

“And because of this good corporate citizenship, Tesco can pay a 4 per cent dividend which is well covered, without the press or the government raising an eyebrow.

“The point that we’re getting at is that, as we’ve seen from the performance of the banks since the financial crisis, being caught on the wrong side of the political and social mood after a crisis can cast a very long shadow. That’s something to think long and hard about in this new environment.”

Data from FE Analytics shows Ruffer Investment Company has made 40.98 per cent over the past decade, compared with 49.56 per cent from its IT Flexible Investment sector.

Performance of trust vs sector over 10yrs

Source: FE Analytics

The trust is on a discount of 0.49 per cent compared with 3.12 and 0.69 per cent from its one- and three-year averages. It has ongoing charges of 1.13 per cent and is not currently geared.