One of Japan’s biggest “flaws” is what helped it sail through 2020’s dividend crisis unscathed, according to Richard Aston, manager of the CC Japan Income & Growth Trust.

The Janus Henderson Global Dividend Index showed global dividends fell 10.5 per cent on an underlying basis (excluding special dividends) in 2020. The UK was one of the worst-hit markets, with the Link UK Dividend Monitor showing domestic payouts dropped 38.1 per cent to £61.1bn.

However, Japanese dividends slipped just 2.1 per cent last year, with just one company in 30 cancelling payouts between April and December, while only a third made cuts.

Aston said the reason for Japan’s resilience is the tendency for its companies to hoard excessive amounts of cash that could be put to better use elsewhere.

“Balance sheets are extremely strong in Japan – that’s one of the criticisms,” he said. “They are not run in the same manner as US companies, for example.

“When we have spoken to companies in the past, they often referred to the fact Japan has faced a good number of crises in the last 20 to 30 years: first its own financial crisis, then it was right on the doorstep of the Asian financial crisis. Next it was affected by the tech crash and on top of those it has had natural disasters as well, with the earthquake and the nuclear accident 10 years ago a prime example.

“As a result of that, they want to be in a position to maintain their business operations and pay their employees, so they feel to some extent justified in maintaining a degree of liquid assets on their balance sheets.”

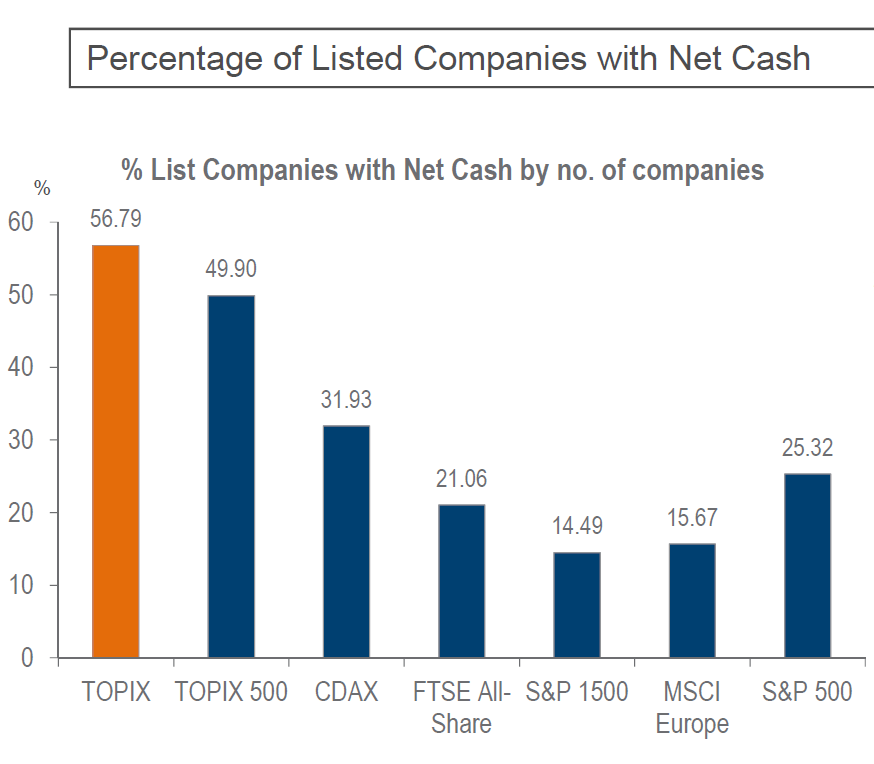

Data from Coupland Cardiff shows 56.79 per cent of companies in the Topix have net cash positions, compared with 25.32 per cent for the S&P 500 and just 15.67 per cent for MSCI Europe.

Source: Coupland Cardiff

Yet Aston said this hoarding culture has begun to change. One of the motivations behind the launch of his trust in 2015 was Abenomics, then prime minister Shinzo Abe’s eponymous programme of structural reforms. This was based around ‘three arrows’, the third of which was encouraging investment, including through a greater focus on dividend payments.

The Janus Henderson Global Dividend Index shows Japanese payouts have grown faster than all other regions except North America since 2009, up 124 per cent. However, Aston said there is still plenty of room for improvement.

“One aspect that we didn't know was how companies would react to the first test [the coronavirus crisis] that they'd faced over the last few years,” he continued.

“On the whole, companies have delivered in that respect. A number are either maintaining or even increasing their dividends year on year, despite the fact that their reported earnings might be down. There are one or two companies that have cut their dividends and some of those are quite interesting as ultimately they were enforced cuts.

“It's been a tough situation, but overall we see this very, very robust profile for dividends in Japan, which gives us great encouragement. It is becoming quite an institutionalised concept, companies are paying very significant attention to shareholders, particularly how they treat them on an annual basis and also expectations going forward.”

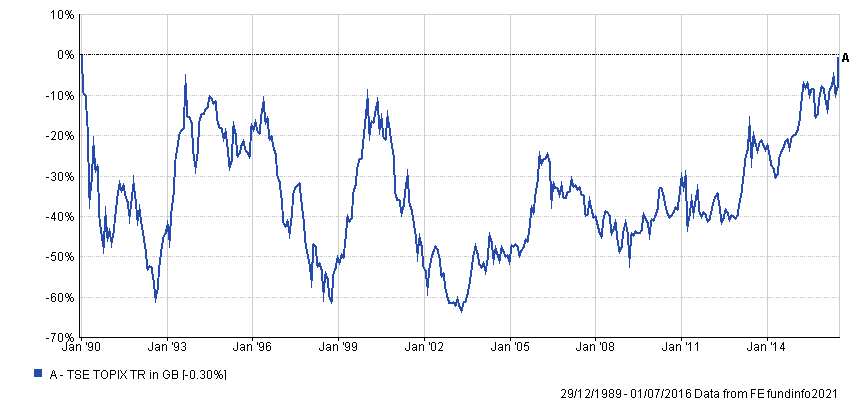

Investors may feel justified in treating Aston’s talk of change in Japan with a hint of scepticism. Someone who bought into the Topix at its pre-crisis peak at the end of 1989 would still have been in negative territory in July 2016. However, Aston said it is important to note the reasons for Japan’s “lost decades” and remember that its companies have not always been so keen on hoarding money.

Performance of index 1990 - 2006

Source: FE Analytics

“There was a period in Japan through the 60s, 70s and 80s, and even most of the 90s, where corporates were basically reinvesting all the cash flows that were generated. It wasn't until around about the Asian crisis or the tech crash that companies in Japan really began to address the issues that had been created by this extended period of overinvesting, which ultimately resulted in the crash,” he explained.

“But as a result of that, back in around 1999 to 2000, it started to reflect on those problems. This included the nationalisation of a number of large banks and the write-down of over-inflated assets. But also some surplus cash flow started to come back to shareholders in the form of dividends and share buybacks for the first time. There wasn't really any dividend culture or any shareholder-return culture in Japan up to that point.”

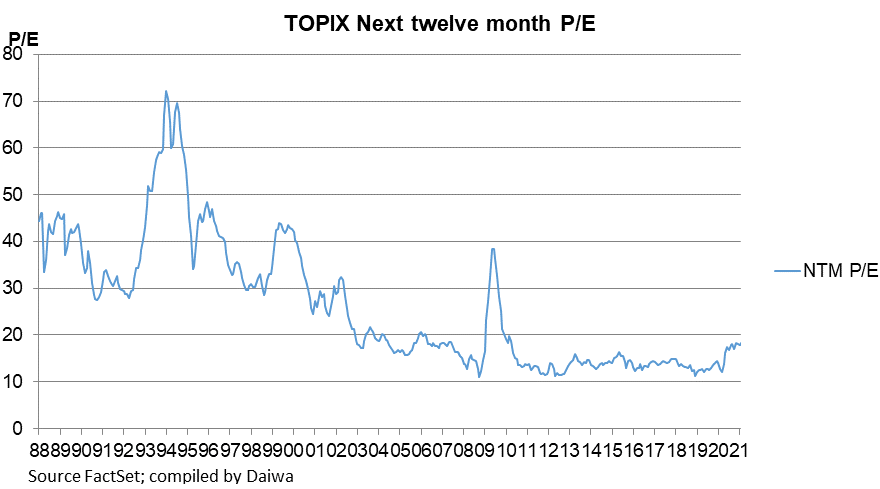

Aston said that the greater focus on shareholders was not the only way in which the mid-2000s marked a turning point for investors in Japan: the region also became attractive from a valuation perspective. He pointed out that up until the financial crisis of 2008, Japan had maintained a “mythical valuation premium” where its companies were always more expensive than their global peers. It was only in the chaos that followed the collapse of Lehman Brothers that it finally de-rated.

“That was very interesting to us because we were Japan specialists, but from a global perspective that was the first time we were able to identify companies in Japan as cheap, or at least comparable to their international peer group,” he said.

“And it was really the valuation, in combination with the confidence we had that companies were more focused on shareholder returns and dividends, that gave us the opportunity to focus on this particular strategy. Then we received quite a strong tailwind in this with prime minister Abe.”

He added: “But in many respects, the opportunity set is greater now than it was even in 2013. The number of companies are in a healthier position and there is this recognition within Japan that corporate governance and shareholder return is important: it's become quite institutionalised.

“We feel as if this strategy has to some extent been verified by the behaviour of Japanese companies, particularly over the last 12 months.”

Data from FE Analytics shows CC Japan Income & Growth has made 52.37 per cent since launch in November 2015, compared with 96.5 per cent from the IT Japan sector and 67.11 per cent from the Topix index.

Performance of trust since launch vs sector and index

Source: FE Analytics

The trust is on a discount of 13.66 per cent compared with 9.75 and 2.91 per cent from its one- and three-year averages.

It is yielding 3.46 per cent and has ongoing charges of 1.06 per cent.