Investors have made higher returns by sticking with markets that have hit a new all-time high rather putting their money in at other times, according to data from Schroders.

This week the UK’s FTSE 100 broke through 9,000, marking a new all-time high for the premier index. It joined the US S&P 500 and Nasdaq indices, which also rose to new records on Monday.

While good news for investors, it may leave some wondering whether the market is near its top and if now is a good time to sell out. But analysis by Schroders of market returns over the past 100 years suggests this could be the wrong thing to do.

The market being at a record high is not an exceptional as some migh think. Of the 1,187 months since January 1926, the market was at an all-time high in 363 of them, or 31% of the time.

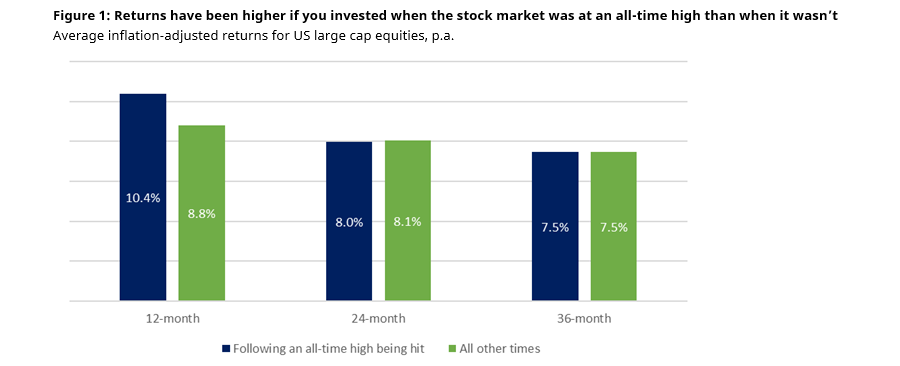

In the 12 months following an all-time high, investors made an average return of 10.4%, compared with 8.8% when markets were not at their peak. After two and three years, the returns are broadly in line with the long-run average, as the below chart shows. The data looks at US large-caps’ average inflation-adjusted returns.

Duncan Lamont, head of strategic research at Schroders, said: “The thought of investing that cash on the sidelines when the stock market is at an all-time high feels uncomfortable. But should it? The conclusion from our analysis of stock market returns since 1926 is unequivocal: no.”

Source: Schroders

There is also evidence to suggest that selling when markets hit new highs (and therefore feel like they may be nearing a peak) is also the wrong thing to do.

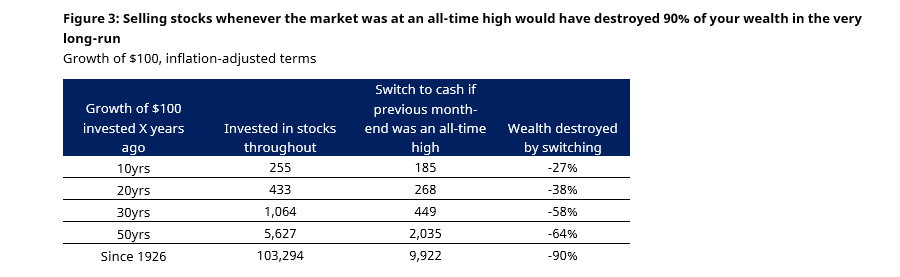

A $100 investment in the US stock market in January 1926 would have been worth $103,294 at the end of 2024 in inflation-adjusted terms.

A strategy that switched out of the market and into cash for the next month whenever the market hit an all-time high (and went back in again whenever it wasn’t at one) would only be worth $9,922, the data showed.

Source: Schroders

Lamont noted: “It is normal to feel nervous about investing when the stock market is at an all-time high, but history suggests that giving in to that feeling would have been very damaging for your wealth. There may be valid reasons for you to dislike stocks. But the market being at an all-time high should not be one of them.”

James Mee, co-head of multi-asset strategies at W1M (formerly Waverton), said: “Bears sound smart, but optimism pays.

“There is always something to be worried about and there will forever be bouts of volatility, but in the long term, prices follow fundamentals.”

Why has the UK hit an all-time high?

Jemma Slingo, pensions and investment specialist at Fidelity International, said part of the UK’s success this year has been due to global factors.

“With geopolitical tensions escalating and Donald Trump’s proposed tariffs rekindling fears of trade wars, investors are looking to diversify away from the increasingly expensive and concentrated US market,” she said.

While many had expected US exceptionalism to continue at the start of the year, US president Donald Trump’s policies have caused this mindset to shift.

“At the same time, several globally oriented UK sectors have delivered strong results,” she noted, such as defence stocks (benefiting from the outbreak of war around the world) and financial services companies (boosted by interest rates).

However, she noted that UK stocks are still “going cheap” despite their strong gains so far in 2025 as they are “notoriously unloved”.

“Data from the London Stock Exchange shows that the S&P 500 trades on a future price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 22.7x. Europe is cheaper at 15x, while the FTSE 100 is cheaper still at 13.6x,” said Slingo.

Why is the US at an all-time high?

The S&P 500 crossed 6,300 on Monday, as corporations are showing strong earnings results in the second quarter of the year.

Stephen Innes, managing partner at SPI Asset Management, said: “What began as a narrative-led rally around AI [artificial intelligence], liquidity and positioning is gradually receiving a shot of validation from corporate America.”

Although only partway through the latest earnings season (12% of S&P companies have reported), “the early indicators are constructive”, with some 83% of stocks beating consensus earnings estimates by nearly 8% on average.

Going into the season, analysts were “notably cautious”, he noted, due to tariff concerns and macroeconomic uncertainty.

“That’s materially above the 10-year average and suggests that many firms effectively managed expectations coming out of the first quarter,” said Innes.

Year-on-year earnings growth has been revised up as a result, he noted, with forecasts for the next 12 months also being moved higher.

“Analysts are beginning to upgrade 2025 and even 2026 numbers – suggesting the rally isn’t merely built on positioning or short covering, but rather on genuine upward revisions to the fundamental outlook,” said Innes.

Part of this is due to a weakening dollar, which is a tailwind for multinationals selling goods and services to other countries.

While valuation remains “a topic of debate”, with the market pricing in at least two rate cuts by the end of 2025, the multiple has room to stretch, especially if earnings growth continues to firm up”.

“In sum, this week’s action feels less like a euphoric melt-up and more like a market that’s methodically validating its gains. That doesn’t eliminate downside risk but it does suggest that the underlying corporate performance is strong enough to warrant current levels, at least for now,” he concluded.