Some investors will have made strong returns over the past few years, as any material weighting to the US market (in particular the ‘Magnificent Seven’ and other artificial intelligence (AI) names) will have likely led to big gains.

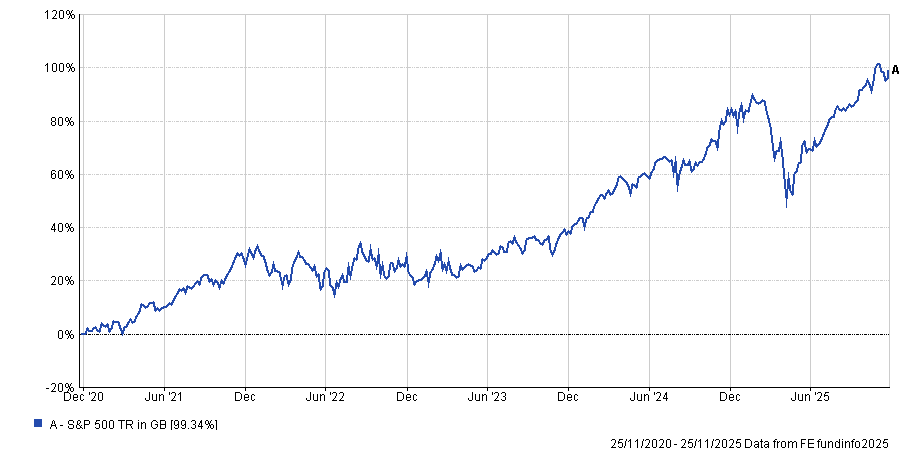

Over the past five years, the S&P 500 has doubled investors' money and, even with a wobble in the first half of the year, the index is up again in 2025.

While strong gains are welcome, they can lead to portfolio dilemmas, according to Ryan Hughes, managing director of AJ Bell Investments.

“For example, if you begin with a portfolio that is 60% equities and 40% bonds, but the equities do much better than the bonds, your portfolio may turn into 70% equities and 30% bonds by the end of the year,” he said.

Performance of S&P 500 over 5yrs

Source: FE Analytics

This may be the case for investors who have high weightings to global trackers (which are dominated by the US market) or who have invested in individual technology holdings.

If a portfolio has become out of line with the initial construction, investors face two choices: decide if this new level of risk is uncomfortable and therefore requires changing; or accept the new levels of risk and let the winners run.

“One of the key things to remember is what you set out to do: you are creating a portfolio, not a collection of ideas,” said Hughes, who noted that although it is nice to appreciate gains, people should look at what they want their portfolio to achieve.

The difficult bit is knowing when to do it. One option for investors is to use the calendar, whether it be quarterly, twice a year, or annually. In this case, people should look at their portfolio and (as long as their goals remain the same as when the portfolio was constructed) rebalance to an acceptable level of risk.

“You trim the winners that have become a larger portion of your portfolio and buy more of the part that hasn’t done as well. This feels painful at the time but it makes sense in the long term,” said Hughes.

The other method available is called a “triggered trade”, whereby investors automatically rebalance when an investment reaches a certain threshold. He said someone with a 60% equity allocation may consider a threshold of 75% to be appropriate, for example.

Rebalancing can be “uncomfortable”, Hughes noted, but it comes with sound financial backing. By selling expensive assets and reallocating to those that have done less well, investors are likely to be moving away from crowded trades and buying temporarily out-of-favour assets at a more attractive price.

“You also aren’t completely abandoning the asset that has done well, just scraping a bit of the cream off the top. Once you rebalance, you’ll be back to the original allocation level – not zero, so if it does go up again, you’ll still benefit,” he said.

Hughes pointed to a study by Wellington Management, which measured the risk-adjusted returns of portfolios that rebalanced versus those where the allocations were allowed to roam free.

“While different rebalancing strategies all gave a ratio of annual return versus volatility of about 0.85, the drifting portfolio's risk-adjusted return sat at closer to 0.75,” he said, suggesting that the rebalancing approach is a safer way for many to invest.

Those unwilling to rebalance themselves may wish to buy a multi-asset fund with a tiered equity weighting, as this puts the onus of portfolio construction in the hands of professionals.