The long-held belief that government bonds represent the ultimate risk-free asset is crumbling, according to Sarang Kulkarni, co-manager of Vanguard’s Global Core and Strategic Bond funds.

Traditionally, sovereign bonds have been viewed as the risk-free benchmark for discounting cashflows, underpinning valuations across global markets.

However, mounting fiscal pressures are eroding investor confidence in sovereign creditworthiness.

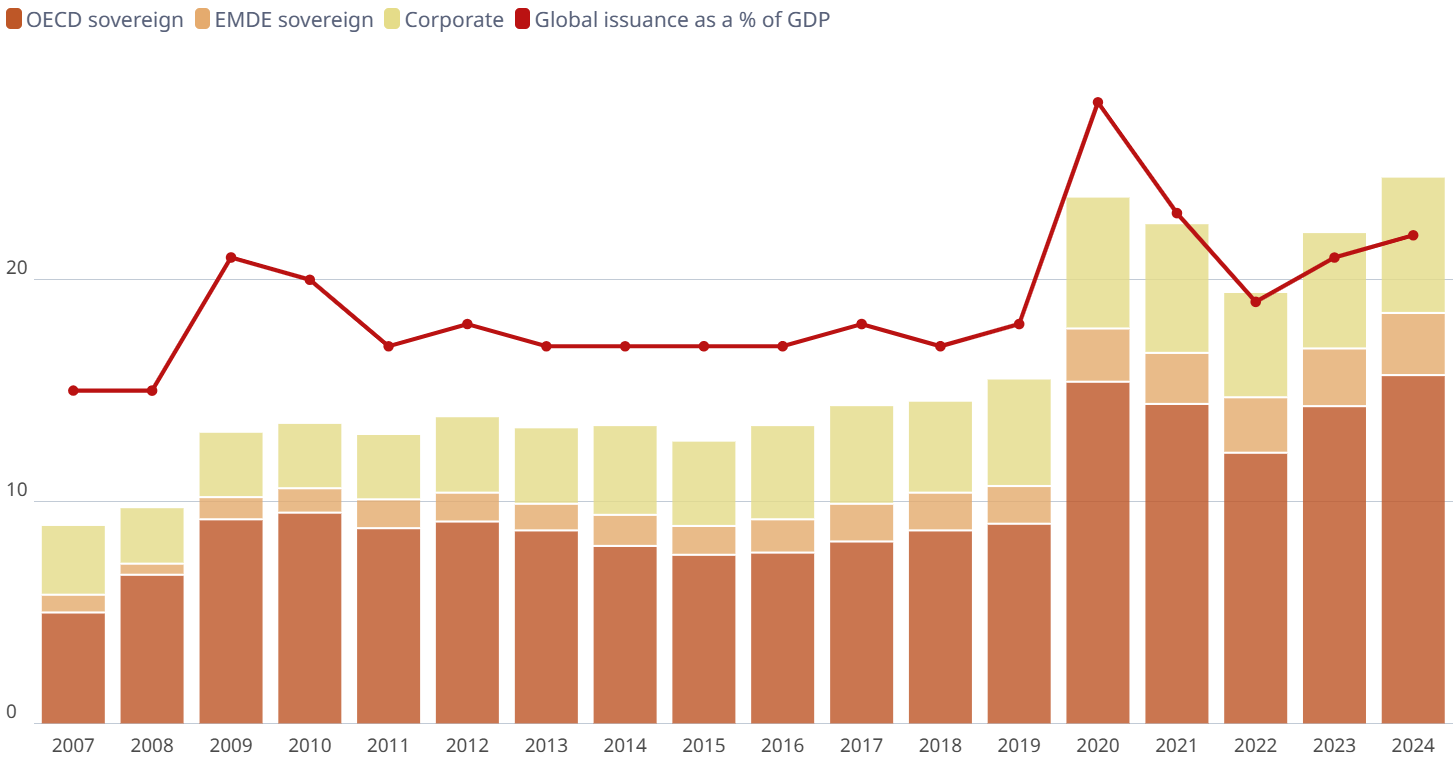

According to the OECD’s Global Debt Report 2025, global borrowing surged to $25trn in 2024, over $10trn above pre-Covid levels and nearly triple 2007 figures. Meanwhile, sovereign debt issuance in OECD countries was $16trn last year and is predicted to hit $17trn by the end of 2025, with refinancing needs reaching $13trn – around 80% of gross borrowing.

As such, outstanding sovereign debt is predicted to reach $59trn in 2025, which pushes the aggregate debt-to-GDP ratio to 85%. This is nearly double 2007 levels.

Attempts by governments to curb debt have so far not been enough to move the needle.

Global sovereign and corporate bond issuance in dollar terms

Source: OECD

This mounting debt burden has led managers like Kulkarni to question why governments are still treated as safer borrowers than corporates with stronger balance sheets.

After all, if a company comes to the bond market but makes no profit and keeps piling on debt, all while management has no support to make any changes to ensure that it is competitive and has a long-term future, most bond managers would likely reject it.

Yet Kulkarni said “this description [applies to] pretty much every sovereign out there at the moment”.

“When I first started working in fixed income, everyone said that the sovereign curve is a risk-free rate. Today, even the market has stopped believing that,” he said.

“Ever since risk-free swaps have been introduced, like SONIA, there has been a gradual and increasing premium between the term structure you have in these swaps versus what you have in the government bond curve. The market is treating government bonds like credit.”

In contrast, corporate bonds have demonstrated “a reasonable amount of fundamental strength” and have remained robust over decades, with balance sheets far stronger than the “ongoing deterioration of government balance sheets”.

This is having an impact on credit spreads.

Credit spreads are essentially the gap between the yields of government bonds and corporate bonds. When spreads are tight, meaning the gap between the two is small, investors feel confident that companies are financially strong and unlikely to default. When spreads are wide (i.e. the gap between the two is bigger), investors see more risk.

Therefore, tighter spreads typically suggest investors see little additional risk in corporates versus sovereigns. As such, many managers want to see wider spreads.

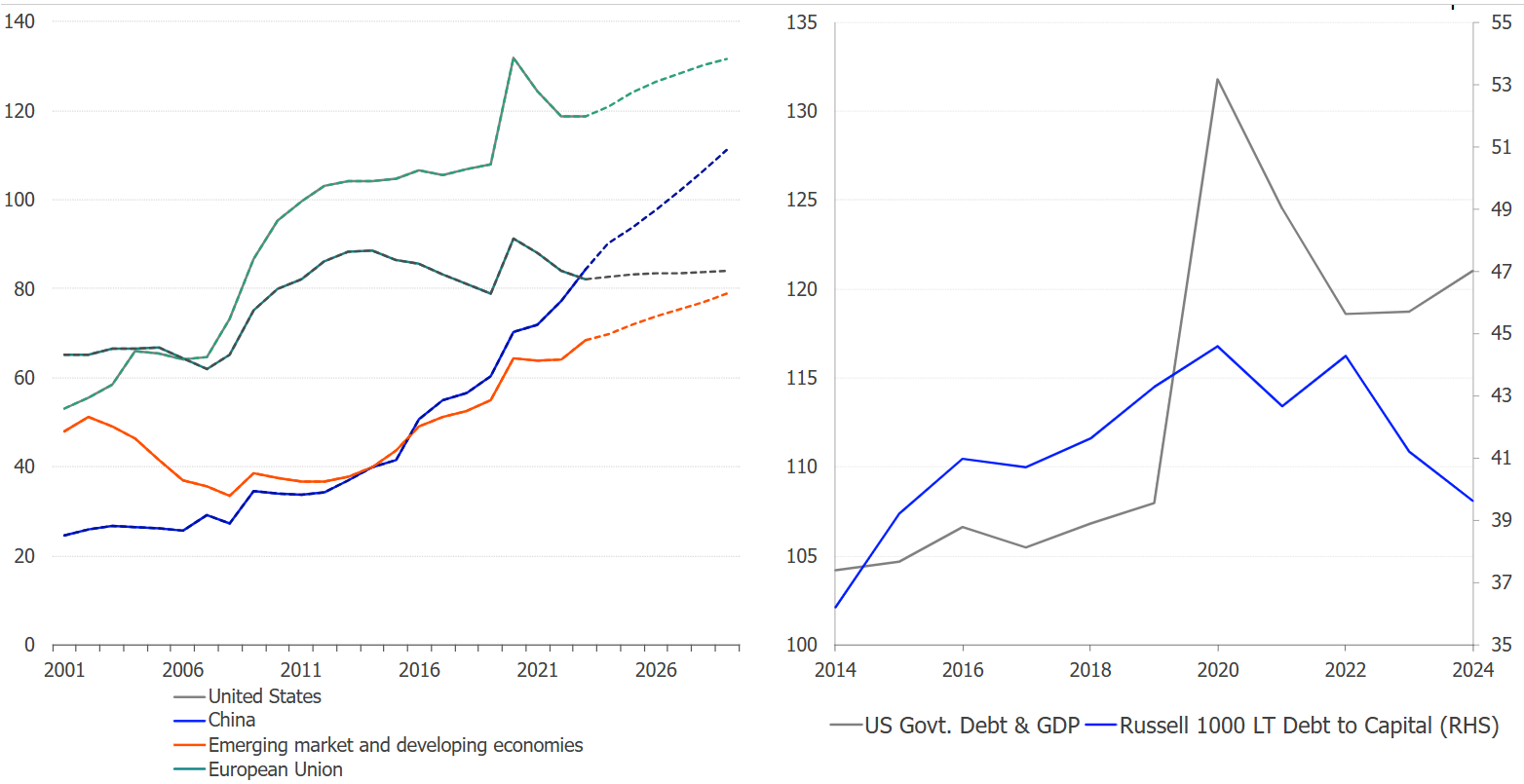

As shown in the left graph below, there is a surge in government bond yields underscoring rising fiscal burdens. The other graph - using the US and Russell 1000 as the example - shows how government debt is rising faster than corporate leverage, which looks more stable.

Government gross debt as a % of GDP and US government debt to GDP vs Russell 1000 long-term debt-to-capital

Source: FTSE Russell, IMF/LSEG. Data as of 31 December 2024.

Kulkarni said that tightening credit spreads are telling a different story than has been the norm – as is shown in the graph above, it seems the issue is more about government bond underperformance.

“Who is to say that credit spreads are too tight?” Kulkarni argued. “They are just a relative value between a corporate and a government. What’s actually happening is the government is getting worse while the corporate is staying where it is.

“During the eurozone crisis, corporate bonds from Italy, Portugal and Spain regularly traded inside their sovereign curves. Even now, this pattern is starting to emerge in US markets.”

If sovereign credit worthiness continues to deteriorate while corporate balance sheets prove to be more stable, then corporate bonds could trade even tighter than current levels suggest, he suggested.

“If you look at a place like Japan, Japanese corporate bonds have traded as tight as 12bps over the sovereign curve, so we still have a long way to go,” Kulkarni said.

“This whole paradigm we have is that sovereigns are the risk-free curve and, through that lens, when you look at corporates they seem tight based on the past. But there is potential for them to go tighter.”