Sovereign debt is no longer useful in multi-asset portfolios due to its negative expected return (if held to maturity) and limited risk mitigation, according to fund managers.

Multi-asset investors have typically favoured government bonds because they provide support when equities fall.

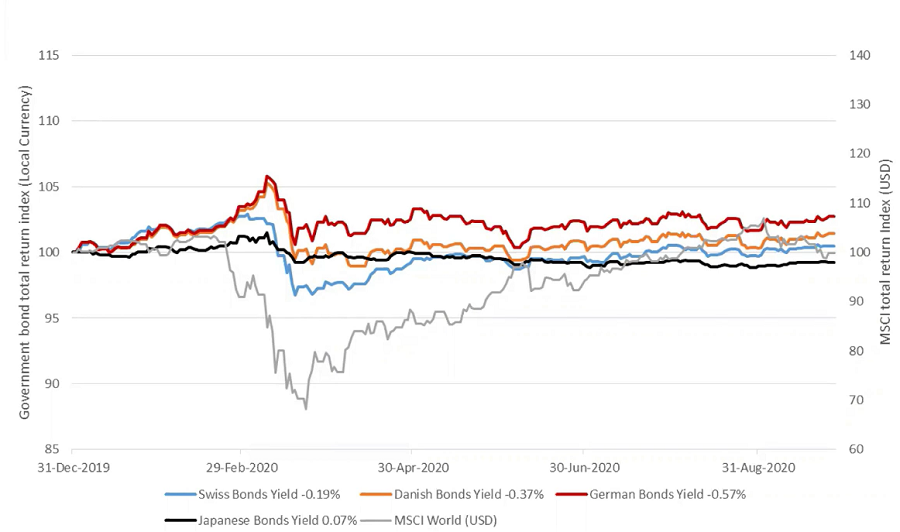

However, John Roe, head of multi-asset at Legal & General Investment Management (LGIM), pointed out that bonds’ potential to rally diminishes as interest rates fall closer to zero. And, although many government bonds surged during the market crash in March, that rally quickly faded.

Phil Smeaton, chief investment officer at Sanlam recalled: “It got to the point where you’d had that knee-jerk reaction of a flight to perceived safety and an appreciation in bonds, then people looked at them and asked, how further into negative territory can these go?

“I’m holding something that if held to maturity is guaranteed to take a loss.”

Performance of sovereign bonds during market stress

Source: Sanlam.co.uk

He added: “So holding government bonds and looking for diversification, looking for them to appreciate during market stress, really failed this time around where they started at zero-to-negative yields, which is where we are in the UK now.

“I think the expectation should be that the historical negative correlation of bonds to equities is not clear at zero bound or below zero.

“In fact, at that point those diversification benefits come under question.”

LGIM’s Roe said that the depths yields can plumb differs by market and is a function of the preferred policy tools of the central bank in question.

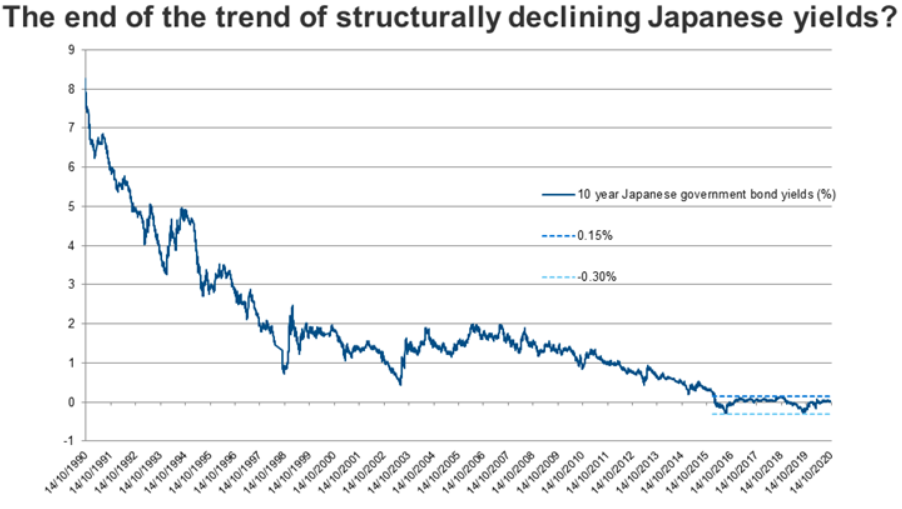

“We feel that Japanese government bonds closed in on the floor years ago, and now their Germany counterparts may be going the same way,” he said.

The manager pointed out Japanese 10-year bond yields fell below zero in 2016 after a decade of dropping and have since trodden a narrow range of 0.45 per cent.

“We think that change in behaviour reflects the perception that there is a barrier in place stopping yields falling much further,” he explained.

“As such, we believe Japanese bonds now offer investors little help during economic or equity downturns.”

He added: “Implied volatility, a measure of the market’s perception of the potential breadth of future outcomes, has similarly collapsed.”

Source: lgimblog.com

Roe explained how German bonds may now reaching a similar status to that of Japanese bonds: “Their yields are already well below Japanese levels, largely because the European Central Bank (ECB) has been prepared to cut interest rates much lower; they are currently -0.5 per cent for the overnight deposit rate.”

Because the ECB surprised markets by not cutting further in 2020, Bunds’ risk-mitigation properties have faded and “with that, their main role in multi-asset portfolios”.

Roe contrasted the 3 per cent returns of 10-year German Bunds with the 10 per cent return from their US equivalents, “which started at much higher yields, and had further to fall”.

The manager expects that other bond markets will face a similar fate in the next few years, which will have meaningful implications for risk management; for example, there will need to be innovative approaches “to plug the gap that high-quality bonds have left”.

He observed that at some points on the yield curve, yields are below 0.7 per cent out to seven years for German Bunds, meaning: “Eurozone investors who hold the bonds to maturity can expect a materially lower return than if they just held cash at current deposit-rate levels.”

Sanlam’s Smeaton said one option investors can take is to sell government bonds and replace them with very short-term corporate credit constructed in a bond ladder, or owning a series of short-dated bonds that expire every three months.

“You can pick up a percentage point of return at a high degree of certainty around that return, because you intend to hold them to maturity,” he explained. “So, we can reduce interest rate risk and increase return.”

AXA Investment Managers’ Nicolas Trindade also said investors now need to look further up the risk spectrum when it comes to cash.

“Keeping cash can be loss-making when you account for inflation, so for investors using it as a strategic asset, the next step up is short duration bonds,” he said.

“Short-duration funds aim to offer higher yields and our own sterling and global funds are yielding 1.3 per cent and 2.2 per cent respectively now, providing a real return even when accounting for inflation.”

The prospect of more negative rates around the world is another reason he believes investors should look beyond cash, with gilts already negatively yielding out to six years.

“Cash already gives you nothing and is loss-making when accounting for inflation, but we could see this worsen if we get negative rates,” he explained.

“Markets will be volatile and the natural reaction will be to go to cash, but investors don’t need to lock-in losses by holding that asset class.

“Short-duration assets are naturally less sensitive to sell-offs and have the ability to recover quickly from any drawdowns, so they provide an attractive alternative to cash,” he finished.